It’s strange developing a sustained transformative relationship with someone you have never met. Perhaps this happens by reading a series of books by a great novelist or studying the lasting theories of a scientist. In the Jewish tradition, the words of our sages are recorded in the present tense.

“Rabbi Akiva says...Rav Huna says in the name of...Rav Yehudah disagrees...”

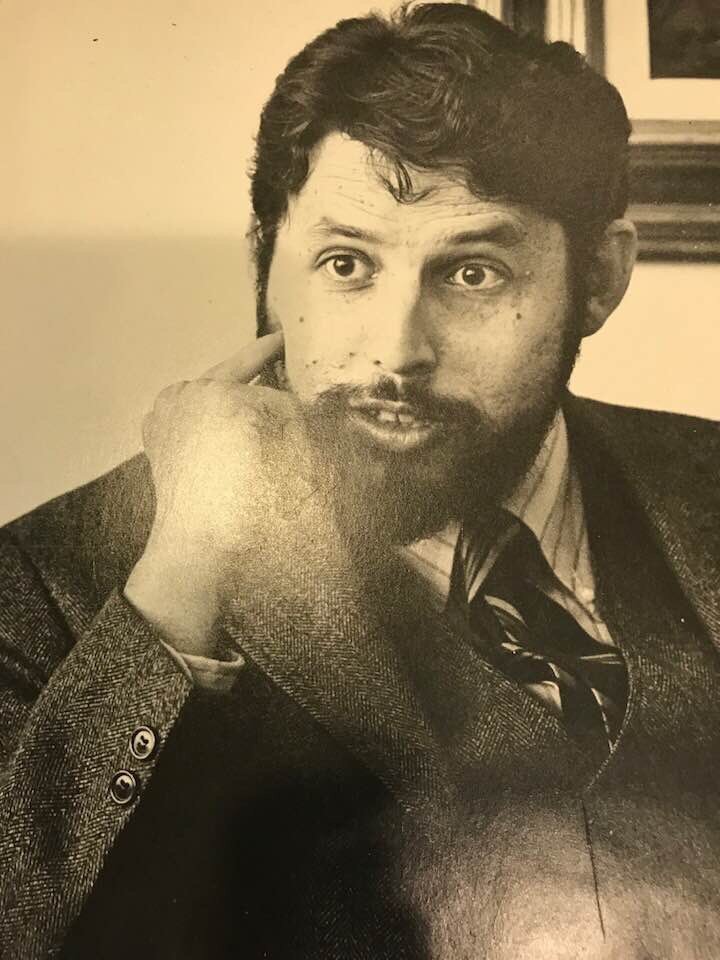

When studying the words of our rabbis it is as if we are part of their conversation and project to build a sacred community. We get to know them through this recorded part of their lives. Since I began dating Adina over 25 years ago, I have been getting to know my father-in-law, Jerry Weber, even though he died a few years earlier. Through the stories about him I have heard and read I have developed my own relationship with him that has shaped who I am.

Adina tells the story about how Jerry never sat still during services. In the main sanctuary, he sat in the back row with his friend Kurt Hirschler where they would kibbitz. In the Library minyan, he would walk around and shmooze. One day, in the middle of services, he gets Eric Iskin’s attention with whom he would often discuss politics, and motions with his finger to follow him. Eric climbs over a row of people, follows Jerry into the hall, expecting a very serious conversation. Jerry says, I just found this great restaurant. Would you and Susan like to join Sally and me for dinner after Shabbat?

This love to make connections between people through the synagogue led Jerry and Sally to help create the Library Minyan at Valley Beth Shalom, a minyan that functioned more like a vibrant Havurah of friends whose lives, families, and homes are still intertwined.

These relationships were nurtured by connecting outside of the synagogue as well, often around the Shabbat table. We have modeled ourselves after Jerry and Sally, opening our home to host people for Shabbat meals throughout our marriage, building a community around Shabbat and through the synagogue.

As a Jewish professional in the Federation, Jerry created the Council for Jewish Life. He created programs to welcome and integrate new immigrants into the LA Jewish community. Jerry used his position and power to include the disenfranchised, especially those with different abilities.

Adina remembers a poster he had in his office of a man in a wheelchair at the bottom of the steps of the entrance of the synagogue. I am inspired by how she draws upon his passion to be a strong advocate for those with different abilities to find their place within the Jewish community.

Jerry also focused internally on the heart of our Jewish community by working with congregations of different movements. Rabbi Danny Landes, the former rabbi of an Orthodox shul, Bnai David, shared with us that when he and Jerry were behind closed doors they argued about everything. However, once they walked into a meeting together they stood shoulder to shoulder working on behalf of the Jewish community. Since I have recently become an employee of the Jewish Federation,

I feel an additional sense of kinship with Jerry as I navigate the challenges of bringing together different Jewish institutions. I emulate his dedication to the larger Jewish community while placing mission over ambition.

Jerry prioritized his family. This can be especially difficult to do for mission-driven Jewish leaders. Adina cherishes the many childhood memories with her father:

While watching the Marx Brothers, he would wildly laugh kicking his feet and hitting the wall behind him.

When they were watching Adina’s Bat Mitzvah tape, Sally was in the kitchen multitasking. At a certain point, Jerry shushed everyone, saying, “It’s the silent Amidah.”

Going to Dodgers games with her father. His photographic mind combined with his love of baseball led to his ritual of showing up to the park early so he could record all of the stats of the game. This wouldn’t prevent him, though, from leaving early to beat the traffic, which always frustrated Adina.

His broad base of knowledge and sharp intelligence allowed him to dominate conversations and Trivial Pursuit games, even against Sally and Muff Singer.

After he died, the family decided they would begin watching movies on Shabbat at home. The first time they put in a video into the VHS it didn’t work.

He went to UCLA where he convinced a few buddies to try out the Young Democrats club with him. Those friends were Former US Representatives Harold Berman and Henry Waxman.

He considered attending USC for graduate school, but his overriding sense of loyalty to UCLA made it impossible for him to even bear being on campus for an interview.

Like the classic father-in-law/son-in-law relationship, part of me is intimidated by him. Do I live up to the ideals and values he emulates? Am I Iiving up to my own ideals and values. While I strive to succeed and be the best person I can be, I also learn from him to accept who I am. He was just a man with his own strengths and limitations, like each of us.

Thank you Jerry Weber for being on this journey with me. It has strengthened me as a husband to your daughter, a father to your grandchildren, a Jewish professional in a challenging Jewish community, and a rabbi with an abiding sense of purpose and mission.

-Rabbi Barkan